![[Francis Naumann]](/4logo.gif)

![[Francis Naumann]](/4logo.gif)

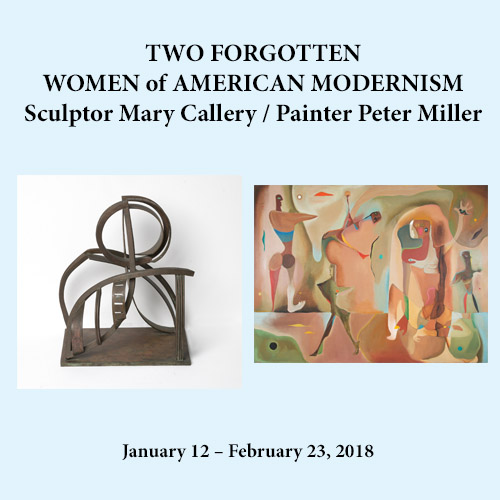

Mary Callery (1903-1977) and Peter Miller (1913-1996) were both well-known artists in the mid-1940s. Callery showed regularly at a number of prestigious galleries in New York in the 1940s and 1950s: Bucholz (1944-1955), Curt Valentin (1947-1955), M. Knoedler & Co. in Paris and New York (1945), and Miller had two well-received one-person shows at the Julien Levy Gallery (in 1944 and 1945), the premier showplace for Surrealism in America. Yet today, with the exception of specialized studies in the field of mid-century American modernism, both artists are absent from historical accounts of the New York art scene in the mid-1940s. There are several reasons for these omissions, one of which may have been gender. Indeed, to counter the prevalent sexism of their day, both artists adopted male pseudonyms: Callery occasionally went by the name Meric Callery, while Miller was born Henrietta Myers, but showed under the name Peter Miller. Another factor that may have contributed to their neglect was the fact that they were both born into privilege, meaning that they did not feel the constraints of having to produce and sell to survive and, therefore, made little effort to promote themselves or their work.

It is unknown if the two artists ever met, but both were born in Pennsylvania (Callery in Pittsburgh; Miller in Hanover, a small town 100 miles west of Philadelphia) and, when they both showed their work in New York in the 1940s, they traveled in similar circles and had several mutual friends. Although separated by 10 years in age, both came to artistic maturity at roughly the same time, in the mid- to late 1930s. Callery took classes at the Art Students League in New York followed by training in Paris, whereas Miller studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. After their formal education, however, both followed very different life paths: by the mid-1930s, Callery had been married and divorced, was living in Paris where she married again and pursued her career as a sculptor, befriending and collecting the work of some of the most notable artists of the day: Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Fernand Léger, Alexander Calder, Aristide Maillol, and others. Miller married in 1935 and, in the years before World War II, she and her husband went on several trips to Paris, where they met Henri Matisse and his son Pierre, Ernest Hemingway, Alexander Calder, Max Ernst, Picasso and, most notably, the painter Joan Miró. It is possibly through Miró—whose work Miller admired—that they were drawn to the city of Barcelona in Spain, which the Millers visited annually. For the remaining years of their lives, however, they traveled more often to New Mexico, where they fell in love with the terrain and built a second home.

Despite these distances, the sources from which Callery and Miller drew inspiration were curiously similar: Callery developed long and sometimes intimate friendships with the artists she knew, particularly Léger, with whom she would even make a number of collaborative works. Miller became increasingly enamored with the work of Miró, and acquired some of his paintings through galleries in New York. In the mid-1940s, Miller became interested in the sand paintings and decorative artifacts made by Native Americans who lived near her home in New Mexico. In 1943 Callery met Georgia O’Keeffe, who was living in Santa Fe and with whom Callery would develop an exceptionally close friendship over the next twenty years (she even purchased a home not far from O’Keeffe’s in Albiquiú). Like Miller and her husband, Callery and O’Keeffe also visited Native American sites, and attended ceremonial dances in the area.

In the 1950s, both Callery and Miller continued their separate careers, each exploring through their respective media the interrelationship between figuration and abstraction. Callery’s sculpture could at times appear entirely abstract, but close inspection often reveals a subject, as in two sculptures—one from the 1950s and another from the 1960s—where the aquatic life she has rendered becomes apparent only after a spectator has been told the title which both sculptures share: Fish in Reeds. Similarly, in a painting by Miller from around 1950, a patchwork of blue textured pigment above a similarly rendered brown field of color appears at first glance to be entirely abstract, until its title, Reef, causes most viewers to look more carefully, whereupon they will discover that Miller has created a scene with small fish swimming at different levels underwater.

In the end, as a comprehensive examination of their work will confirm, there are more differences between these artists than similarities, yet there is no question that they both faced obstacles that would contribute to their having been forgotten over time. The present exhibition is intended to begin the process of reexamining their work anew, in hopes that it can be properly integrated and assessed within future accounts of American art of the 1940s and 1950s.